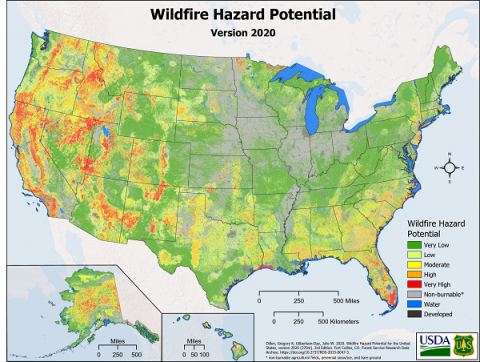

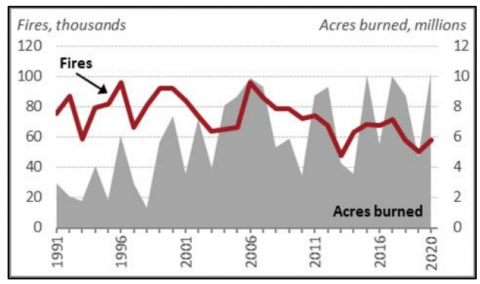

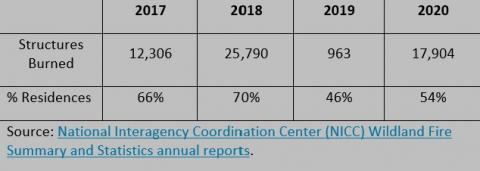

Wildfires have been in the news a lot in recent years, darkening the skies and threatening suburban and even urban centers (Figure 1). Wildfires can occur anywhere in the United States, but are especially prevalent in the drier, mountainous western United States (Figure 2). While the number of wildfires occurring annually has decreased slightly over the past 30 years to about 70,600 wildfires per year over the past 10 years, the number of acres burned has doubled, averaging 7.0 million acres burned annually since 2000, up from an average of 3.3 million acres succumbing to wildfires annually in the 1990s (see Figure 3, Congressional Research Service (CRS) 2021). In 2020 alone, 10.12 million acres burned, making it the second worst year for acres burned since 1960 (CRS 2021). Some states have been hit worse than others. California saw 4.3 million acres burn in 2020 in six of the top 20 largest wildfires recorded in the state (CALFIRE 2021). While the majority of this acreage is on public lands, wildfires pose a serious threat to human life and property, particularly in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), the transitional areas where human development and wildlands meet. Across the United States in 2020, wildfires claimed 17,904 structures, 54% of them homes (see Table 1). The California 2020 wildfires alone claimed 10,500 structures and 33 lives (Insurance Information Institute (III) 2021).

A recent study by the U.S. Forest Service found that, from 1990 to 2010, the amount of WUI area in the United States grew rapidly from 224,000 square miles to nearly 300,000 square miles. For scale, the 76,000-square-mile area of WUI expansion over those 20 years is larger than the state of Washington. The expansion of the WUI poses challenges for wildfire management with more buildings and human life at risk to wildfires. The U.S. Fire Administration estimates more than 46 million residences in 70,000 communities throughout the United States are at risk for WUI fires. The growth in WUI poses two problems. First, increased human activity in the WUI will lead to more human-caused wildfires. Second, wildfires that occur pose an increasingly greater risk to lives and property and are more difficult to fight.

Firefighters approach urban and suburban fires differently from wildland fires. In urban and suburban areas, most house fires start from within the home, primarily due to cooking fires, or heating equipment or wiring problems. The strategy used by fire fighters is to get to the house as quickly as possible (generally within 2 to 5 minutes of receiving the call) to attack the fire aggressively and keep it at a room-and-contents level (PNNL 2021). If the crew can reach the home within that short window of time, there is a strong likelihood they can save the home. Builders can help increase survivability in the event of a housefire in urban and suburban settings by installing smoke detectors and carbon monoxide detectors, providing adequate means of egress, and constructing the home to modern building codes which require firestopping, fire-blocking, draft-stopping, thermal barriers, and ignition barriers like solid lumber and gypsum sheathing in the building assemblies.

Homes located in the wildland urban interface present some different realities that must be recognized. Remote locations, limited access, and difficult terrain all contribute to longer response times for volunteer or paid firefighting crews and once there, water resources may be limited, with firefighters relying on the water in their tank trucks, nearby ponds or lakes, cisterns or swimming pools if the home has one, or water relayed by fire crews from distant sources (PNNL 2021).

Once ignited, it only takes 10 to 15 minutes for a house fire to become established and spread throughout the home, making it unsalvageable. Fire crews responding to a structure fire in the WUI may count the house as unsaveable by the time they reach it and, depending on the situation, they may turn their attention to preventing the fire from spreading to surrounding structures or vegetation (PNNL 2021).

The guides in this section of the Disaster Resistance tool will focus less on structural fires caused from within, by cooking, heating or electrical malfunctions, and more on the threat that comes from outside, the threat of wildfire to homes located in the WUI. These guides focus on measures builders and home owners can take to increase the home’s chances of surviving even without suppression activities by firefighters because, during a wildfire conflagration, firefighters may not be available or able to protect the home, based on time, distance, conditions, and other firefighting activity.

Homes located in the wildland urban interface are at risk of fires caused by lightning strikes, embers from burning debris or untended campfires, fallen power lines, sparks from vehicle accidents or equipment malfunctions, cigarettes, fireworks, and arson (USFS 2018). Burning embers are actually the biggest cause of wildfire spread. Embers from burning trees or structures can be carried a mile or more on the strong winds created by wildfires. They can land on dry leaves and pine needles collected in roof gutters and valleys or at the base of walls where they might ignite the exposed edge of the roof or wall sheathing. Or the embers might get stuck between deck boards or in cracks along wood siding or fascia where they can smolder for hours before catching the house on fire. Embers can get drawn into attic vents or open or broken windows where they can ignite curtains and furniture to burn the house down. Windows can break due to radiant heat from burning trees or shrubs near the home. The wildfire can ignite vegetation or debris around the home or flammable elements of the structure although direct contact with the fast-moving fire front itself is a less common cause of home ignition (Figure 4).

Homes located in the wildland urban interface are at risk of fires caused by lightning strikes, embers from burning debris or untended campfires, fallen power lines, sparks from vehicle accidents or equipment malfunctions, cigarettes, fireworks, and arson (USFS 2018).

Homeowners may feel hopeless in the face of an oncoming fire but there is actually a lot that builders and homeowners can do in advance to improve the survivability of a home in wildfire-prone areas. They can select a home site in topography that is more protected from wildfire-spreading winds. They can establish defensible space around the home with landscaping that is planned to minimize fuel near the home. And, they can construct the home to increase its fire resistance by minimizing combustible surfaces.

Wildfire Guides

The following guides provide information on making the components and assemblies of a home more resistant to wildfires.

Roof

- Metal Roofs

- Clay or Concrete Tile Roofs

- Asphalt Shingle Roofs

- Vented vs Unvented Attic

- Roof Vents

- Gutters and Downspouts

Walls/Windows/Doors

- Moisture-, Impact-,Fire, and Pest-Resistant Exterior Siding

- Fire-Resistant Wall Assemblies

- Windows Have Impact-Rated Glass, Fire-Resistant Glass, or Protective Coverings

- Exterior Doors are Impact Rated and Fire Rated

Building Attachments

Foundation/Site

Operations/Equipment

Design

More Info

The following authors and organizations contributed to the content in this Guide.

Building Science Corporation

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory