Scope

Install indoor fire sprinklers to improve protection against injury and loss of life during a fire.

- Design and install a multipurpose plumbing system, which serves domestic water fixtures and indoor fire suppression sprinklers, or a stand-alone fire sprinkler system, to suppress fires within the home.

- Install a “wet” sprinkler system within the home where the pipe can be maintained at or above 40°F. If the sprinkler piping will be routed through unconditioned space where temperatures may drop below 40°F (for example in a vented attic), install a stand-alone piping system (not connected to the home’s potable water supply) that contains an approved pre-mixed antifreeze solution or install a dry pipe system, where water only enters the pipes due to a loss of pressure when sprinklers are activated or a pre-action system, where water only enters the pipes when enabled by a supplemental detection system.

- Ensure fire sprinkler coverage is in accordance with NFPA 13D, i.e., sprinklers are installed in all living areas, except as noted.

- Space sprinkler heads in accordance with the minimum specified by the manufacturer but not less than 8 feet apart, as required by NFPA 13D.

- Use CPVC piping or PEX tubing for fire sprinkler water distribution. Use metal piping where exposed.

- Install a backflow prevention device and water meter where required by the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ).

- Install a pump if using a standalone non-pressurized storage tank or where municipal water pressures are inadequate.

See the Compliance Tab for links to related codes and standards and voluntary federal energy-efficiency program requirements.

Description

Indoor sprinklers for fire protection are a type of automated extinguishing system (AES) and are an important life safety measure in homes. If a fire occurs in a specific room of a home equipped with sprinklers, the heat-sensitive element in the sprinkler head in that room is triggered and releases water to suppress or restrict the growth of the fire, containing it to the room of origin. A report published by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA 2017) found that from 2010 to 2014, flame damage was confined to the room of origin in 97% of fires where sprinklers were present, compared to 74% of fires without a sprinkler system. The NFPA report also found that the civilian death and injury rates were 81% and 31% lower in homes with sprinklers, and the firefighter injury rate was 79% lower in homes with sprinklers. The presence of indoor sprinklers gives occupants more time to escape the home and helps manage the intensity of the fire until first responders arrive on the scene – increasing the survivability of the home and its occupants.

Indoor fire sprinklers can also increase the wildfire resistance of a home and should be considered for homes in wildfire-prone areas, such as in the wildland urban interface (WUI). Interior sprinklers can be effective in containing interior home fires due to wildfires. Even if the exterior of the home does not ignite, firebrands, airborne debris, and convective heat can enter a home through vents, open or broken windows, and other openings, resulting in ignition from within. In addition, homes in the WUI are often located in remote areas far away from fire departments where firefighter response times are longer. Indoor sprinklers can help manage the fire until the firefighters arrive on the scene.

Although fire sprinkler systems are effective, they are not common in residential applications. According to the 2011 American Housing survey, only 5% of occupied housing units were outfitted with sprinklers. To increase the adoption of fire sprinklers in the residential sector, in 1975 the National Fire Protection Association introduced the Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems in One- and Two-Family Dwellings and Manufactured Homes (NFPA 13D). The NFPA 13D standard is primarily focused on life safety. NFPA 13D was designed to be a cost-effective residential sprinkler solution. It reduces costs by allowing the omission of sprinklers in less-critical areas such as in small closets, bathrooms, and garages. A study by the Fire Protection Research Foundation (2013) Home Fire Sprinkler Cost Assessment-2013, found that the average cost to install sprinklers in new homes in 2013 was $1.35 per square foot of sprinklered area on average. To put this into perspective, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB, Ford 2020) found that the average construction cost of a home in 2013 was $95 per square foot, which means that the installation of sprinklers in a new home was roughly only 1% of the total cost of construction. In addition, installation of fire sprinkler systems may potentially decrease the homeowner’s insurance rates, leading to increased savings over the life of the home.

Classification of Fire Sprinkler Systems

There are two general classifications for fire suppression sprinkler systems: standalone or multipurpose systems. As defined in NFPA 13D Chapter 3, standalone systems are fire sprinkler systems where above-ground piping for the fire sprinklers is separate from piping that serves potable water taps in the home. Some jurisdictions do not allow the use of standalone systems because they require more maintenance and can be shut off independently of the domestic water supply. NFPA 13D Chapter 3 defines multipurpose systems as piping systems that are intended to serve the home’s domestic water fixtures as well as the home’s fire protection needs. The network of piping in multipurpose systems serves both sprinkler heads and potable water fixtures in the home. NFPA 13D allows for both standalone and multipurpose systems, although multipurpose systems are generally recommended because they typically require less maintenance and tend to be more reliable. Any problems with pipes that supply the sprinkler system will likely be noticed because those same pipes serve other domestic plumbing fixtures in the home, which are likely to be used daily. Because they are connected to the home’s potable water supply, multipurpose systems must be approved by the local plumbing or health authority.

NFPA 13D, Chapter 9, makes a distinction between “wet” and “dry” sprinkler systems. The majority of sprinkler systems are wet systems. A wet system is plumbed so that the piping always contains water up to the sprinkler heads. Wet systems are preferred to dry systems as the water is in the pipe ready to be immediately dispersed. Wet systems can be used if the sprinkler pipe can be maintained at or above 40°F.

If the sprinkler piping will be routed through unconditioned space where temperatures may drop below 40°F (for example in a vented attic), NFPA 13D, Chapter 9, specifies that the sprinkler piping could be set up as a dry pipe system or a pre-action system. NFPA 13D defines a dry pipe system as a sprinkler system that employs automatic sprinklers attached to a piping system containing air or nitrogen under pressure, the release of which (as from the opening of a sprinkler) permits the water pressure to open a valve known as a dry pipe valve, and the water then flows into the piping system and out the opened sprinkler. NFPA 13D also defines a pre-action system as a sprinkler system that employs automatic sprinklers that are attached to a piping system that contains air that might or might not be under pressure, with a supplemental detection system installed in the same area as the sprinklers.

As an alternative to a dry pipe or pre-action system, in locations where the sprinkler pipe cannot be maintained at or above 40°F, the sprinkler piping can be set up as a stand-alone system (one not connected to the home’s potable water supply) that contains an approved premixed antifreeze solution in the pipe fluid. This antifreeze solution will have a percentage of propylene glycol or glycerin.

Fire Sprinkler Locations

NFPA 13D requires fire sprinkler coverage of all areas within a dwelling, except where specifically exempted. NFPA 13D, Chapter 8.3, lists the following exceptions:

- Bathrooms of 55 square feet or less.

- Clothes and linen closets, and pantries of 24 square feet or less and where the walls and ceiling are surfaced with noncombustible or limited-combustible materials as defined in NFPA 220.

- Garages, open attached porches, carports, and similar structures.

- Attics with or without storage, penthouse equipment rooms, elevator machine rooms, concealed spaces dedicated to and containing only dwelling ventilation equipment, floor/ceiling spaces, elevator shafts, crawl spaces, and other unoccupiable spaces.

- Covered, unheated projections of building entrances as long as the dwelling unit has another means of egress.

- Closets in garages and exterior closets located on exterior balconies, exterior breezeways, and corridors accessed from outdoors where the closet does not have doors or unprotected penetrations into the dwelling unit. However, sprinklers should be installed in closets housing heating and/or air-conditioning equipment, washers and/or dryers, or water heaters, unless those closes are outside or in a garage as noted.

- Ceiling pockets that meet the following conditions:

- The total volume of all unprotected ceiling pockets in a compartment does not exceed 100 cubic feet.

- The entire floor under the unprotected ceiling pocket is protected by the sprinklers at the lower ceiling elevation.

- The interior finish of the unprotected ceiling pocket excluding decorative treatments is noncombustible or limited-combustible material.

- Skylights not exceeding 32 square feet are permitted to have a plastic cover.

Components of a Fire Sprinkler System

Components of an indoor fire sprinkler system include the water supply, the pump, the trim, and the piping, as well as the sprinkler heads themselves.

Sprinkler Heads

Residential sprinkler heads come in four different styles: pendent, concealed, sidewall, and concealed sidewall as see in Figure 2. Residential sprinkler heads are rated at different temperatures that are typically limited to ordinary temperature rating (135°F to 170°F) or intermediate temperature rating (175°F to 225°F) as defined in NFPA 13D, Chapter 4.1. These temperature ratings determine the range in which the sprinkler heads will activate. Ordinary-rated sprinkler heads are used in rooms where the maximum ambient ceiling temperature does not exceed 100°F. Intermediate-rated sprinkler heads are used in rooms where maximum ambient ceiling temperatures are between 101°F and 150°F. Intermediate-rated heads may be used to adjust for specific heat sources, such as if exposed to direct sunlight, in an unventilated concealed space under an uninsulated roof or attic, or near other heat sources like fireplaces or furnaces.

The minimum flow of water from a sprinkler head is determined by a set of calculations: the first involves the listed sprinkler discharge coefficient and minimum pressure and the second involves the floor area and discharge density. The discharge coefficient, or k-factor, varies depending on the orifice diameter of the sprinkler and is generally between K2.8 and K8.0 for residential style sprinklers. NFPA 13D, Chapter 8.1, specifies a minimum operating pressure of 7.0 psi, or the listed minimum pressure of the sprinkler head, whichever is greater. NFPA 13D, Chapter 10.1, specifies a minimum discharge density of 0.05 gpm/ft2 or the listed discharge density of the sprinkler head, whichever is greater.

In the first calculation, the minimum flow, Q, is found by multiplying the k-factor, k in gpm/psi1/2, by the square root of the minimum pressure, P in psi, as shown in Equation 1. In the second calculation, the minimum flow, Q, is found by multiplying the minimum discharge density, D in gpm/ft2 and the area covered by the sprinkler, A in square feet, as shown in Equation 2. The minimum sprinkler flow should be the greater of the two calculations.

| Q(gpm) = k√P | (Eqn. 1) |

| Q(gpm) = D × A | (Eqn. 2) |

Water Supply

For automatic fire sprinkler systems, the water supply should also be automatic as specified in NFPA 13D, Chapter 6.1. The water supply can be either a pressurized tank, a non-pressurized tank with a pump, or the municipal water supply. Where a water storage tank is used, the minimum capacity of the tank should be determined based on the system’s water demand rate. Sprinkler systems that comply with NFPA 13D are designed to protect against a fire originating from a single location. It is assumed that only the sprinklers in a single location will activate. This means that the system water demand rate is not found by adding the flows for all sprinkler heads, but instead is determined by adding the required flow for up to two sprinkler heads serving a specific area. The minimum capacity of the storage tank as specified in NFPA 13D is the system demand rate multiplied by ten minutes, or for single-story dwellings less than 2,000 square feet, the minimum capacity of the storage tank can be reduced to the system demand rate multiplied by seven minutes. For example, if one large room in a 1,500-ft2 single-story home requires three sprinkler heads that have a required minimum flow of 26 gpm each, the system demand rate would equal 52 gpm and the minimum capacity of the storage tank can be calculated as 364 gallons (52 gpm x 7 minutes).

Pump

For a non-pressurized system, or where the available water pressure is not enough to deliver the required flow at the necessary pressure, an electric pump shall be used. The pump does not have to be fire protection listed, but it must be listed by Underwriters Laboratory (UL) for electrical safety. The pump should be located no less than 1.5 inches off the floor, any means for disconnecting the pump shall be approved, and a test connection shall be provided downstream of the pump. Additionally, if the pump uses AC power, it shall be rated for 240 volts and wired in accordance with the National Electric Code (NFPA 70).

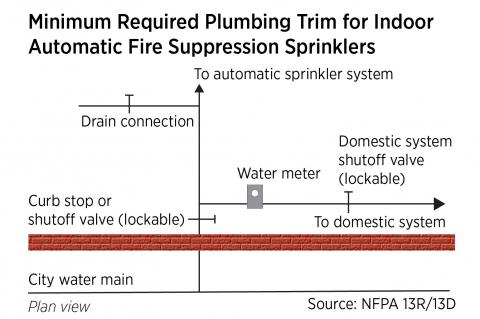

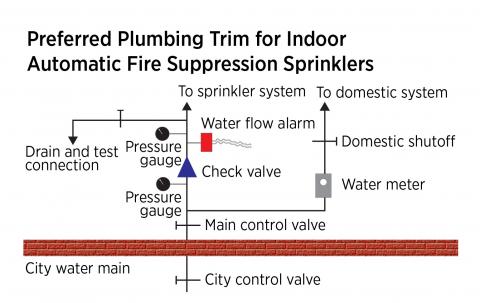

Trim

The schematic drawing in Figure 3 shows the minimum required plumbing fittings (trim) for a standalone system using municipal water. As seen in Figure 3, a minimum ½ inch drain connection and valve are required on the system side of the control valve to allow for maintenance, testing, and sprinkler replacement. Figure 4 shows the preferred plumbing trim and connections for a standalone system using municipal water. Some jurisdictions require a back-flow preventer or a check valve, although it is not required by NFPA 13D. Check with the local authority having jurisdiction to confirm if backflow prevention is required with your design. Pressure gauges on either side of the backflow prevention device allow for visual inspection of the functionality of the system. In addition, a waterflow alarm can be installed to alert the homeowners and local fire department that the fire sprinkler system has been triggered.

Piping

Sprinkler piping should be sized to provide the required system water demand rate as determined through hydraulic calculations or through the prescriptive method found in the International Residential Code (IRC), Section P2904. NFPA 13D, Chapter 5, specifies allowable piping materials. Although the standard allows for the use of copper, steel, or thermoplastic piping, the most economical piping material that should be used in single-family homes is thermoplastic. The available options for thermoplastic piping are chloro-polyvinyl chloride (CPVC) and cross-linked polyethylene (PEX). CPVC, shown in Figure 5, is the most commonly used piping material in residential applications and is relatively low cost. It is important to use the correct type of glue for CPVC connections to ensure that all joints and fittings meet the pressure requirements listed in NFPA 13D. PEX has also become increasingly popular because it is flexible and is easier to install with fewer connections; however, connecting PEX tubing involves crimping or clamping the connections which requires special tools that can be difficult to maneuver in tight spaces.

Insulating Pipes and Air Sealing Ceiling Penetrations

Sprinkler piping is often located in vented attics and the sprinkler heads therefore represent penetrations through the ceiling separating the conditioned space of the home from the unconditioned space of the attic, which could provide opportunities for heat loss into the attic. If possible, limit building envelope penetrations by running sprinkler piping inside interior walls, using sidewall sprinklers, or running sprinkler piping in soffits within the building envelope. Where sprinkler piping must be run outside of the building envelope, such as in an unheated attic, ensure that the piping is appropriately insulated using the arrangements listed in NFPA 13D Appendix A.

Common methods for insulating fire sprinkler piping in an unheated attic are the “box-in” and “tenting” methods, shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. In the box-in method, boxes are made to cover the pipes out of drywall and/or rigid foam that is sealed with caulk or tape at all seams and sealed to the drywall of the ceiling with tape, caulk, or canned spray foam. With the tenting method, foil- or paper-backed insulation is tented over the piping, then stapled to the trusses or rafters (paper side down) and taped or caulked to the ceiling deck. The box-in method is a more robust method for bringing the fire sprinkler pipe within the building envelope. Another method is to install the sprinklers in a dropped ceiling chase or soffit that is below the ceiling which serves as a continuous air barrier above the irrigation sprinkler piping.

Some types of sprinklers are designed to pop open and cannot be caulked. Make sure to check the sprinkler manufacturer’s installation instructions for your specific model of sprinklers. When installing concealed sprinklers, make sure that the cover plates and escutcheons fit snugly against the wall or ceiling to reduce the likelihood that future homeowners will try to caulk them to the drywall. In general, air sealing should not be performed around sprinkler heads. Instead, it is preferable to bring the fire sprinkler pipe within the building envelope through construction of a dropped soffit or a sealed chase as shown in Figures 6 and 7, where air sealing occurs above the piping or around the chase and not at the interface of the sprinkler head and the drywall.

Success

Check state and local codes regarding design and installation of residential fire sprinkler systems. Historically, fire sprinkler requirements for residential fire sprinkler systems have been met with resistance due to perceived high installation costs or homebuilder liability concerns. Some concerns have been raised about their installation in remote and Wildland Urban Interface areas where firefighter crews might not reach a home to shut off the water once the sprinklers have been activated possibly causing more water damage than fire damage to a home.

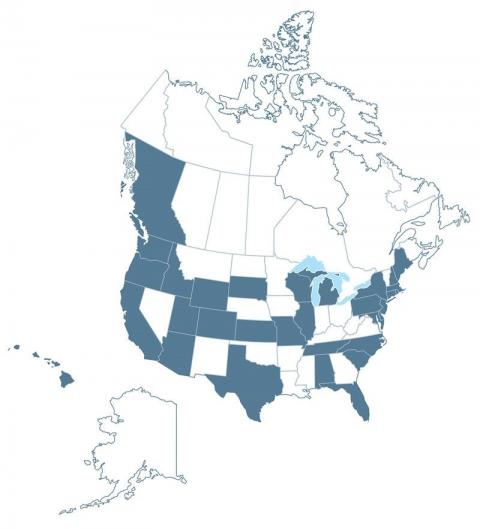

Currently California, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. require fire sprinklers in new, one- and two-family homes and have adopted provisions of NFPA 13D. There are 29 states that prohibit statewide or local adoptions of fire sprinkler requirements, and 19 states that allow local adoption of fire sprinkler requirements for new, one- and two-family homes. In addition to these state codes, many municipalities, especially those located in the wildland urban interface (WUI), have adopted municipal code ordinances regarding fire safety, in some cases more restrictive than those adopted by the state.

Verify fire-related code requirements with the municipality having jurisdiction over your building site.

Climate

The U.S. Forest Service offers a website with interactive maps and charts to help communities explore wildfire risk in their location.

The National Fire Protection Association provides a website with information regarding state- and province-based fire sprinkler coalitions. Check the map in Figure 1 to see if the state where the home is located has an active fire sprinkler coalition. These fire coalitions provide useful resources with a local focus.

Training

Compliance

Compliance

Consult the local or state fire agency or qualified building code specialist about state and local codes, standards, requirements, and amendments related to automatic fire sprinkler systems.

International Energy Conservation Code (IECC)

International Residential Code (IRC)

Retrofit

Scope

The International Residential Code (IRC) Section R313.2 requires automatic residential fire sprinkler systems to be installed in all new one- and two-family dwellings, but does not require them for additions or alterations to existing buildings that did not already have a fire sprinkler system. As local code may vary from the model code, check with local codes to see if fire sprinklers are required in a retrofit of an existing home.

Description

If adding fire suppression sprinklers to an existing home is required by local code for a renovation or addition or is desired by the homeowner, follow the guidance provided in this guide for new construction. Note that any sprinkler piping that is installed in unconditioned space, such as a vented attic, must be insulated and air sealed as described in the Description tab and in NFPA 13D, Appendix A Chapter 9, CPVC Fire Sprinkler Piping 2021 and Sprinkler Insulation: A Literature Review 2011.

More

More Info.

Access to some references may require purchase from the publisher. While we continually update our database, links may have changed since posting. Please contact our webmaster if you find broken links.

The following authors and organizations contributed to the content in this Guide.

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory