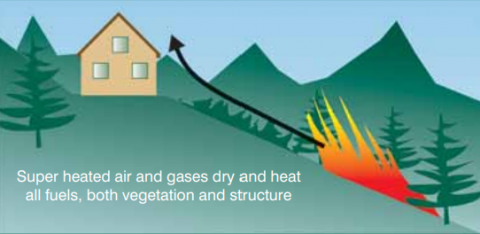

Homeowners may feel hopeless in the face of an oncoming fire (Figure 1), but there is actually a lot that builders and homeowners can do in advance to improve the survivability of a home in wildfire-prone areas. They can select a home site in an area with topography that is more protected from wildfire-spreading winds. They can establish defensible space around the home with landscaping that is planned to minimize fuel near the home. They can also design and construct the home to minimize combustible surfaces and combustion-prone features on the exterior of the home.

Siting of the Home

Good wildfire defense begins with siting of the home. FEMA provides the following guidance to help builders and property owners to reduce the potential for damage when choosing a home site in the wildland urban interface (WUI) (FEMA P-737 2008).

- Avoid selecting a construction site along a gully or in a narrow canyon.

- Avoid selecting a construction site in or adjacent to a saddle or narrow mountain pass.

- Avoid constructing a home adjacent to or on a steep slope (Figure 2). If a ridgetop site is selected, choose an area that allows for a minimum 50-foot setback from wildland vegetation on the downslope side.

- Increase the setback at sites with heavier fuels such as in a forested environment.

- Orient the narrowest wall of the building toward the likely path of a wildfire to minimize the risk of structural ignition.

- Orient the building based on wind and fuels so that debris, embers, and firebrands are less likely to accumulate next to the building’s walls, especially near the inside corners of entries and other off-set walls.

- Minimize the number of windows on the side of the building facing the likely path of a wildfire to reduce the risk of radiant heat or firebrands and flying debris breaking the windows.

- Establish defensible space around the building.

- Provide two-way access to the house and turn-around space for fire-fighting vehicles near the home.

Defensible Space

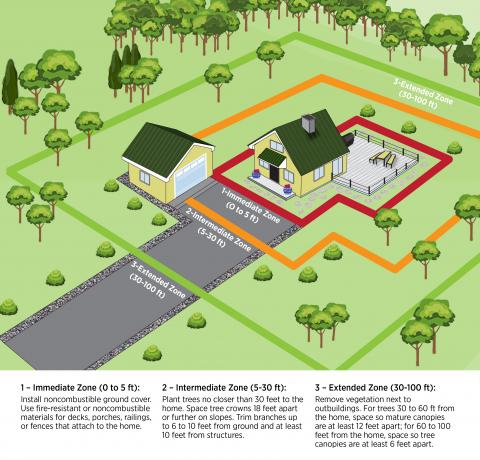

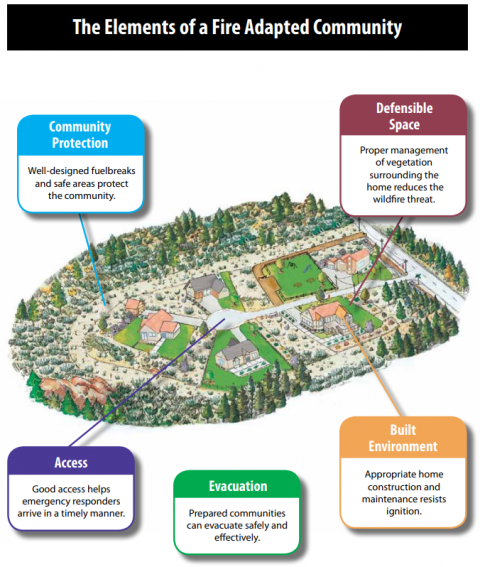

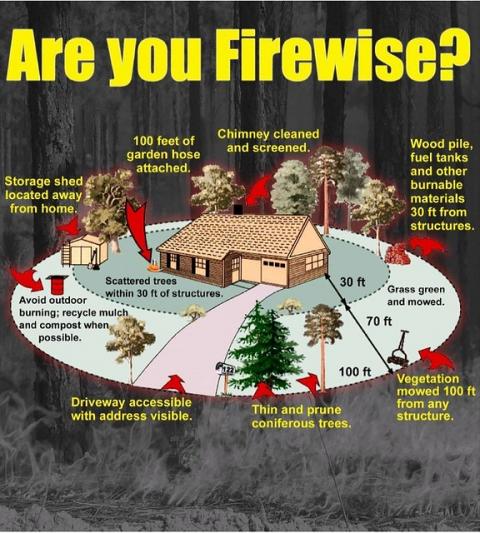

Wildfires need fuel to spread. That can take many forms, including live or dead vegetation, outbuildings, and the home itself. The area surrounding a home where fire fuel, such as vegetation, has been managed to mitigate the spread of fire is referred to as defensible space (Figure 3). Defensible space is one of the most important factors in determining a home’s ability to survive a wildfire (Figure 4) and a key determinant in whether fire crews can safely approach the home to defend it in a wildfire. For more information, see the Solution Center guide "Defensible Space."

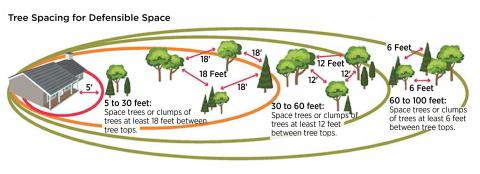

To create defensible space on residential properties, establish zones of lower combustion risk around the home by thinning or removing vegetation closer to the home (Figure 5) (NFPA 2021, IBHS 2019):

- Immediate Zone – 0 to 5 feet, the “Noncombustible Zone”

- Use noncombustible ground covers.

- Remove all trees and shrubs and overhanging branches.

- Employ noncombustible materials and construction practices for all structures and attachments.

- Intermediate Zone – 5 to 30 feet, the “Clean and Green Zone”

- Clear the site and keep or plant only individual deciduous trees or clusters of two or three trees allowing for at least 18 feet between canopies of mature trees or clusters. Allow more spacing if trees are on sloped ground.

- Remove ladder fuels – shrubs under trees, low branches up to 10 feet.

- Employ maintained lawn and noncombustible ground cover fuel breaks.

- Extended Zone – 30 to 100 feet, the “Reduced Fuel Zone”

- At 30 to 60 feet from the perimeter of the house, space trees and tree clusters for at least 12 feet between canopies of mature trees.

- At 60 to 100 feet from the perimeter of the house, space trees and tree clusters for at least 6 feet between canopies of mature trees.

- Trim branches back 10 feet from each side of access roads.

Beyond Extended Zone – Where property extends beyond 100 feet from perimeter of a community of homes (see Figure 6).

- Thin trees.

- Prune ladder fuels.

- Employ green strips and shaded fuel breaks around the perimeter of the extended zone.

Lower-Fire-Risk Construction

Even in places where homes are closer together, structures can survive wildfires if the home is constructed of fire-resistant roofing, siding, and windows, with enclosed soffits and decks and with minimal vegetation near the structure. The home shown in Figure 7 survived a wildfire that rose up from a wildland ravine and destroyed the homes on either side of it and on the slope above because this home incorporated fire-resistant features.

Here are several steps builders can take to improve the fire resistance of a home (CAL FIRE 2021, UCCE 2021, IBHS 2021). Some of these features are shown in Figure 8 from the Insurance Institute for Building and Home Safety (IBHS). Many of these steps are described in more detail in the guides in this section of the Solution Center.

Design

- Consult local code requirements.

- Hire a licensed architect or engineer to develop a detailed approach for fire resistance.

Roofs

- Use Class A-rated roofing materials like clay tile, concrete tile, slate, metal roofing, or fiberglass asphalt shingles.

- Roof coverings can have a Class A, B, or C rating.

- Class A products are the most fire resistant.

- If curved roof tiles are used, close off the ends with bird-stopping materials to prevent birds and rodents from building nests which can be a fire fuel source.

Attic Vents

- Use ember and flame-resistant vents.

- Screen all attic vents with wire mesh or hardware cloth with openings no larger than 1/8 inch.

- Don’t use fiberglass or plastic mesh that could melt or burn.

- Install soffit vents on fascia or nearer to the edge not the house.

- Consider an unvented attic design.

Chimney

- Cover the chimney opening with a non-flammable screen with openings between 3/8 inch and 1/2 inch to prevent embers from escaping.

Eaves and Soffits

- Box in eaves or install flat (horizontal) soffit coverings that are noncombustible like fiber cement or ignition-resistant like fire retardant-treated wood.

- Cover roof edges with metal drip edge that extends into the gutters to cover the edge of the flammable roof decking and keep out embers.

Gutters

- Cover gutters with gutter screens to prevent the accumulation of leaves and pine needles.

Siding and Cladding

- Use ignition-resistant siding materials such as fiber cement, stucco, masonry, or brick veneer.

- Cover the underside of cantilevered wall sections with non-combustible cladding.

- If constructing the walls with a ventilation gap behind the cladding, install screening at the top and bottom of the walls to keep embers and bugs out of the air gap.

Exterior Doors

- Use fire-rated noncombustible or solid wood doors.

- If the door contains windows, they should include one layer of tempered glass.

Windows

- Use dual-pane windows that include one pane of tempered glass.

- Replace damaged wood frames.

- Ensure that vinyl windows have a metal-reinforced central vertical bar in slider windows or horizontal bar in single- or double-hung windows.

- Install metal bug screens in openable windows; they can provide some protection against radiant heat.

Decks

- Use heavy timber or noncombustible materials for supports, deck surface, and railings.

- Screen or box-in areas below decks to prevent debris accumulation.

- Set decks back from the top of slopes covered by unmaintained vegetation.

- If the deck is located above a steep slope with unmaintained vegetation, consider installing a noncombustible wall and patio to separate the deck from the slope.

Garage

- Install weather stripping at sides and top of the garage door and a sweep at the bottom to keep out embers.

- Add a battery back-up to the garage door motor in case the power goes out.

Fences

- Use noncombustible materials for at least the 5 feet of fencing closest to the house.

Hose Bibs

- Install easy-to-access hose bibs on the front and back of the house and equip with 100 feet of garden hose.

Driveway and Access Road

- Ensure the driveway or lane can accommodate two-way traffic.

- Maintain space for an emergency vehicle turnaround.

- Ensure gates open inward and are wide enough to accommodate emergency vehicle access.

- Clear trees and shrubs 10 feet back on each side of the driveway with no overhanging branches. Make the address visible from the road.

Cistern or Swimming Pool

- If there is no nearby natural year-round water source like a pond, lake, or river, consider installing a cistern, well, or swimming pool as a source of water for fire suppression.

Indoor Sprinklers

- Install indoor sprinklers if required by code or desired by homeowner.

Automatic Gas Shutoff Valve

- If the home is connected to a gas line, install an automatic gas shutoff valve such as an excess flow valve and/or earthquake-activated shutoff valve if required by code or desired by the homeowner.

Smoke Detector and CO Monitor

- Install smoke detectors and CO monitors as required by code.

- Supply a fire extinguisher.

Defensible Space

- Determine a site clearing and landscaping plan to establish defensible space around the site.

- Provide the homeowner with guidance on less combustible ground covers and plants.

- Recommend to the homeowner steps for ongoing maintenance, like the steps shown in Figure 9 from the wildfire education program FireWise from the National Fire Protection Association.

Climate

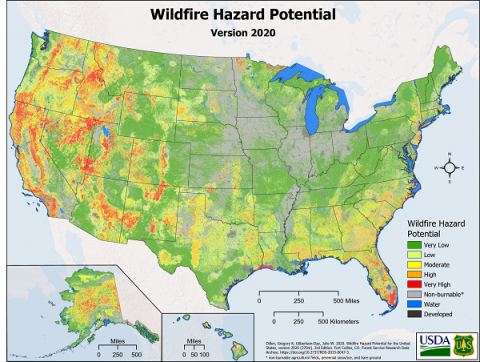

Wildfires have historically been common in the mountains and western parts of the United States during the summer and fall months. However, wildfires can occur anywhere where vegetation is plentiful. See the map of wildfire potential in the United States (Figure 10).

The U.S. Forest Service offers a website with interactive maps and charts to help communities explore wildfire risk. Homes built in wildland-urban interfaces in hot and dry climates are especially susceptible to wildfire events. Proper creation of defensible space is even more important in these areas to minimize the risk of home ignition and slow the spread of wildfire within the community.

Specific wildfire risks vary by region and are dependent on topography, native vegetation, building styles, and the quality of state and local building codes. The Insurance institute for Business and Home Safety® (IBHS) provides regional guides that offer region-specific guidance, best practices, and voluntary standards for creating defensible space (IBHS 2021).

Definitions

Many terms are used when discussing wildfires. Some of these have specific meanings in codes although The following definitions are from the article “Fire Ratings for Construction Materials” by Stephen Quarles of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS 2019). See the article for more extensive explanations of the testing procedures for each term. Also see the factsheet “Fire Code Terminology Related to Fire Tests” (MN State Fire Marshal 2016).

Noncombustible - A noncombustible material is one that is not capable of undergoing combustion under specified conditions (ASTM E 176), for example metal, concrete, and stone. These materials provide the best performance in terms of both flame spread and penetration.

Fire Resistance and Fire-Resistant Construction – These materials rely on the assembly rating for resistance to fire penetration and the exterior material (i.e., the one that would be exposed to the fire) for information regarding flame spread. The flame spread rating of a material is determined by placing the material in a horizontal tunnel and subjecting it to a gas flame. A combustible material will be rated as Class A, Class B, or Class C (1, 2, or 3) based on its performance in this test. A material rated as Class A would have a lower flame spread, and therefore a better performance rating, than a Class C material. The classes are defined in the bullet list above.

Ignition Resistant - In most parts of North America, “ignition-resistant” is not defined so it can mean different things to different people. The International Code Council’s International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC) and the California Building Code (CVC) have defined ignition-resistant materials as those meeting a minimum flame spread rating after being subjected to a specified wetting-drying weathering cycle. California defines a material as “ignition resistant” if it has passed the 30-minute test. an example of an ignition-resistant material is exterior-rated fire-retardant lumber, i.e., lumber that has been pressure impregnated with a fire retardant that has been rated for use on the exterior of a building.

More Info

The following authors and organizations contributed to the content in this Guide.

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory